Fred wanted to post an ad for a job on Craigslist and to add some photos of his workplace. Unfortunately, he didn’t know how to do it. So he wrote to them. He points us to this response he got from Craigslist, usually renowned for its tech support:

Unfortunately, we don’t offer image hosting for the following categories:

* jobs

* gigs

* services

* resumes

If you’d like to add an image to a post in one of those categories, you’ll

need to upload the image to a server somewhere else, then add HTML code to

your post that references that image. (more bad news — we don’t provide

tech support for this task.)

Thanks,

craigslist customer support

Anytime you send someone a note like this, where you basically say, "we’re not going to help you, go away," you’re doing something unnecessary. Don’t tell them to go away, tell them where to go. Worse, if you do it when the person is about to buy something (in this case a help wanted ad) you’re leaving money on the table as well.

Posting a picture for an ad on Craigslist is so common that they’ve got boilerplate for the letters they get asking for help. So why not have a FAQ page for it? (All you need to do is google Craigslist Picture Hosting to learn how… you could write the FAQ in five minutes.) Then, at the bottom of the FAQ, it’s easy to say, "We don’t support this, but if you have trouble, here are three or four forums where people might be able to help you…"

We now live in a do-it-yourself world. You can ask customers to buy their own tickets, fill out their own forms, support their own software. But pointing them to resources will buy you a lot of loyalty. (And save you a lot of grief).

March 19, 2007

Evolution of advertising:

We buy ads. You must watch them.

We buy ads. You have a remote control. You skip them.

We buy ads. You are watching a cable channel.

We send junk mail to your house and spam to your inbox. You delete it.

uh oh.

[Internet]

We buy banner ads, you ignore them.

We buy AdWords ads. We pay by the click. Wow! It works.

And that’s where we were until today. The most effective online ad buy is AdSense ,where you bid for traffic and pay by the click. This is permission-based, because your ad shows up next to a Google search or on a relevant page. So the people who are seeing it are the right people. And the click demonstrates that they want to see your page.

The paradox (not necessarily a bad thing) is that the better your ad, the better your offer, the more you pay.

So we invented SquidOffers, which I hope will work for us, and which I fully expect will show up in other places soon. The idea is to combine the voting mechanism of Reddit or Digg or Plexo with the text ad mindset of a Google ad. But instead of an ad, it’s an offer.

Make an offer. Pick a category. Pay a small fee ($100 a month). Then, our users vote on the offers. Get a lot of votes and you rank more highly, which means more clicks. And you don’t pay for the clicks.

Now there’s an incentive to write better and better offers (but they need to be genuine or we boot you). Offer a free sample or a free issue or a consult or an ebook. Be generous. Get permission to follow up.

Over time, we intend to raise the rates as volume increases. For now, a few days into it, it appears to be working. Here’s the info.

March 16, 2007

Is George Clooney actually a great actor?

Or is he just great at making choices?

In 1789, you had just a few choices. Work for the potter in town, apprentice with your dad, of, if you were really smart, become a clergyman or possibly a teacher. That was it.

Today, not only do you have more choices, the variations in those choices matter more. Obvious choices, like, "should I quit my job today?", necessary choices like, "should I apply for a job at Google or an insurance company?" and more subtle choices–whether or not to start a blog, for example.

The movie business provides us with a clear window on what happens when people make good choices (and bad ones). Very few people–with the exception of Sean Connery or Daniel Craig–have the option of sticking with one movie forever. Everyone else in the industry makes critical choices on a regular basis. Smart choice makers do far better than those that don’t work at it. I’m willing to guess the value of smart choices is responsible for a 10 to 100 times difference in lifetime earnings in Hollywood.

I think the same is true for a career in programming, marketing or just about anything else. If you’re in the position to start a company, why didn’t you do it a year ago? Why not now? If you’re a programmer, why didn’t you apply to work at YouTube when the getting was good? If you’re a marketer, how are you going to spend your time and your money? Not choosing is still making a choice.

Tim Cook, Apple COO:

The traditional way that all of us were taught in business school to

look at a market was you look at the products you are selling, you look

at the price bands that are in the market, you think of the price band

that you product is in and assume you can get a percentage of it, and

that’s how you get this addressable market. That kind of analysis

doesn’t make really great products. The iPod would not have been

brought to market if we had looked it that way. How many $399 music

players were being sold at that time? Today the cell phone industry, a

lot of people pay $0 for the cell phone. Guess why? That’s what its

worth! If we offer something that has tremendous value that is sort of

this thing that people didn’t have in their consciousness, it was not

imaginable… I think there are a bunch of people that will pay $499 or

$599 and our target is clearly to hit 10 million and I would guess some

of those people are paying $0 because its worth $0 and willing to pay a

bit more because its worth more.

Short version: creating the best cell phone in the world required being willing to charge for it. And if you can make a cell phone worth charging for, people will pay it. Apple’s Dip was working their way through a barrier (charging) that no one has felt willing to make such a huge bet on before.

I now firmly believe that there are two polar opposites at work:

Thrill seekers and

Fear avoiders

Notice that I don’t use the word ‘risk’ to describe either category. More on that soon.

How do we explain the fact that Forbes finds more than 700 billionaires and virtually none are both young and retired? Why keep working?

How do explain why so many organizations get big and then just stop? Stop innovating, stop pushing, stop inventing…

Why are seminars sometimes exciting, bubbling pots of innovation and energy while others are just sort of dronefests?

I think people come to work with one of two attitudes (though there are plenty of people with a blend that’s somewhere in between):

Thrill seekers love growth. They most enjoy a day where they try something that was difficult, or–even better–said to be impossible, and then pull it off. Thrill seekers are great salespeople because they view every encounter as a chance to break some sort of record or have an interaction that is memorable.

Fear avoiders hate change. They want the world to stay just the way it is. They’re happy being mediocre, because being mediocre means less threat/fear/change. They resent being pushed into the unknown, because the unknown is a scary place.

An interesting side discussion: one of the biggest factors in the success of the US isn’t our natural resources or location. It’s that so many people in this country came here seeking a thrill.

So why not call them risk seekers and risk avoiders? Well, it used to be true. Seeking thrills was risky. But no longer. Now, of course, safe is risky. The horrible irony is that the fear avoiders are setting themselves up for big changes because they’re confused. The safest thing they can do now, it turns out, is become a thrill seeker.

Who do you work with?

March 15, 2007

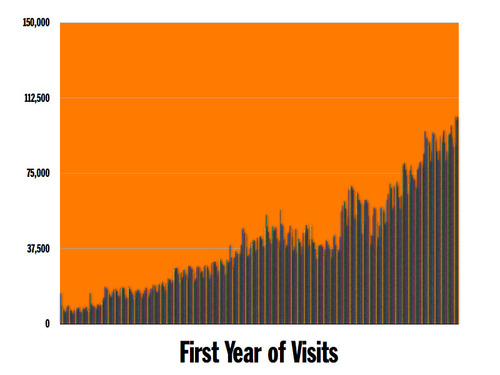

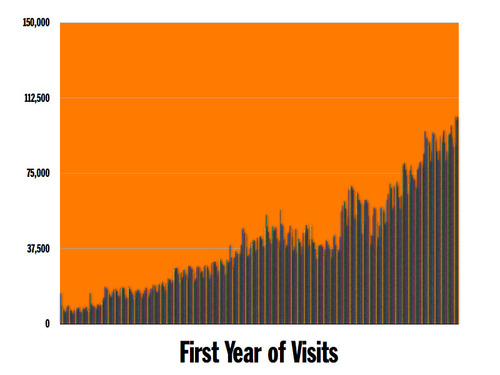

Today, Squidoo hit 100,000 lenses. In a few hours, we’ll hit 50,000 unique lensmasters as well. That’s as good an excuse as any to talk about what we’ve learned.

In no particular order:

- It takes longer than you think it will. Daily traffic is 10 times higher than it was a year ago. That’s a huge number. Seduced by the legendary stories of overnight web successes, we thought it would happen in a month. Patience is a virtue.

- People learn by example. As the lenses getting built get better, it inspires others to do better stuff too. Highlighting great work is a critical step for any community.

- Bad actors are everywhere. And most of them will go away if we focus on eliminating anonymity.

- Google matters. Yahoo and Ask too. Not manipulative SEO, but honest pages that benefit users if they get found.

- The community is smart. Really smart. They run large parts of the site, and they do it beautifully.

- You don’t need VC money if you plan around it. The emphasis is on the second part of that sentence. Other than attending a small trade show, we didn’t spend a penny on outbound marketing, nor did we flog it far and wide.

- You don’t need many people, but is sure helps if you hire people who are brilliant, honest and passionate.

- Temptation is everywhere. Temptation to artificially boost traffic or revenue or some other metric. It might work in the short run, but when you’re done, you don’t have much to show for it.

- Bizdev is dramatically overrated, either that or we’re bad at it. The growth of Squidoo has come from individuals (99%) not corporate partners.

- What you start with is wrong. At least what we started with was. Fortunately, we planned on being wrong, and have revamped most aspects of what we built. Tomorrow I’ll be posting on our new ad approach.

If you want to see what’s working, here are three things to try:

Lloyd points us to Makers of Splenda buy Hundreds of Negative Domain Names. The idea, I guess, is to keep someone from writing something nasty about Splenda.

Is there enough money in the world to buy enough domain names to keep a determined person from saying something nasty about Splenda?

Monopolies work to protect something that wouldn’t belong to them if we had a chance to start over. Everyone else works to provide services or goods that people actually want.

Gil just sent this one over:

[Blake just sent me this note: "The reason it is free is because they put their switches in independent telephone companies (rural America) when a larger phone company terminates a call (when you call the “free” conference calling) then the rural company is able to charge Qwest or whomever else terminates the call a fee. In areas like IA they want to buy the LD for .05 cents a minute and then charge Qwest as high as .15 cents a minute for terminating the call. They want to buy it for less then it costs. This is a common practice in this sector of the industry but they have found a way to milk the system and do more then it was intended to do and are in this case killing the larger Telco companies if that makes sense." It’s entirely possible he’s right. If so, I apologize to Cingular, etc.–the challenge those companies face is pretty obvious–we don’t get phone service so we can call most phones, we get it so we can call all phones.]

I’ve been listening to Live at Massey Hall: Neil Young and thinking and even crying a bit. It’s an awfully powerful piece of work.

Two lessons for marketers, one small, the other bigger. First, it’s interesting to note how much more excited and open the crowd is to songs they’ve heard before. Even some of the songs that ended up becoming classics got a tepid reaction because they were unknown at the time.

Second, on songs that aren’t working so well, you will hear Neil try harder, play louder, raise his voice and strain to make an impact. It doesn’t work. At all. It’s what you say, most of the time, not how you say it.

March 14, 2007

I went to trade in my

I went to trade in my car Jay Porter Prius for an updated Prius today. Well, I meant to do that, but I walked out instead.

I arrive at Westchester Toyota and pass two or three salespeople loitering outside. Inside, there were two or three more, sitting in a line of chairs, waiting for the signal from the headmistress at the counter.

My guess is that even for a thriving brand like Toyota, most of these guys weren’t paid so much. They were ‘good’ salespeople, lifers who showed up, did what they were told and closed a sale here and there.

It soon became clear that the salesperson who was assigned to me wasn’t ‘great’. The dealership had messed up: He had no record of my appointment, no file, no history of why I came. But he just punted. He made no effort to engage with me or look me in the eye or empathize with my frustration at the complete waste of time my call yesterday had been. He gave up after about ten seconds, bummed out that he had lost his place in line. So I left.

Driving home, I started to think about the discontinuity in the graph of salespeople. Discontinuities are interesting, because that’s where you can see how a system works. In this case, it’s obvious that a great salesperson is going to sell far, far more than a good one. Nine women working together can’t have a baby in one month, and ten good salespeople still aren’t going to close the account that a great one could. That’s because it’s not a linear scale. The great ones reach out. They work the phones when they’re not first in line. They understand what a customer wants. They’re not just better than good. They’re playing a totally different game.

My best advice: Fire half your salesforce. Then, give the remainder, the top people, a big raise, and use the money left over to steal the best salespeole you can find from other industries or even from your competition. You’ll end up with fewer salespeople. But all of them will be great.

And the good guys? Have them go work for the competition.

March 13, 2007

I went to trade in my

I went to trade in my