Today, Squidoo hit 100,000 lenses. In a few hours, we’ll hit 50,000 unique lensmasters as well. That’s as good an excuse as any to talk about what we’ve learned.

In no particular order:

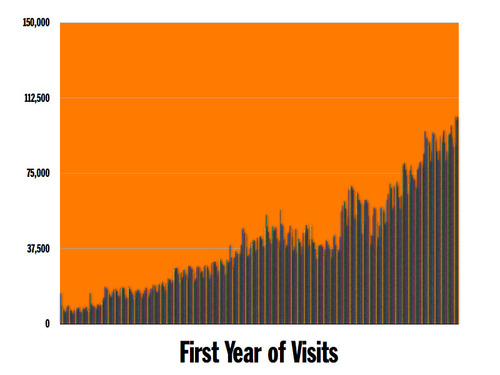

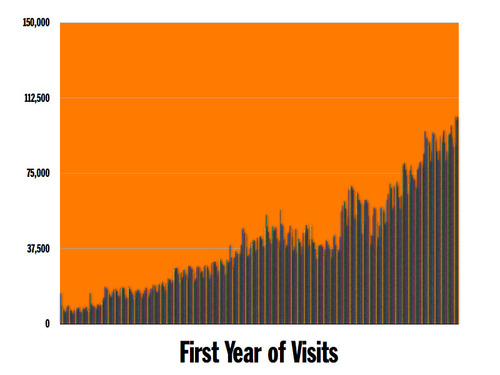

- It takes longer than you think it will. Daily traffic is 10 times higher than it was a year ago. That’s a huge number. Seduced by the legendary stories of overnight web successes, we thought it would happen in a month. Patience is a virtue.

- People learn by example. As the lenses getting built get better, it inspires others to do better stuff too. Highlighting great work is a critical step for any community.

- Bad actors are everywhere. And most of them will go away if we focus on eliminating anonymity.

- Google matters. Yahoo and Ask too. Not manipulative SEO, but honest pages that benefit users if they get found.

- The community is smart. Really smart. They run large parts of the site, and they do it beautifully.

- You don’t need VC money if you plan around it. The emphasis is on the second part of that sentence. Other than attending a small trade show, we didn’t spend a penny on outbound marketing, nor did we flog it far and wide.

- You don’t need many people, but is sure helps if you hire people who are brilliant, honest and passionate.

- Temptation is everywhere. Temptation to artificially boost traffic or revenue or some other metric. It might work in the short run, but when you’re done, you don’t have much to show for it.

- Bizdev is dramatically overrated, either that or we’re bad at it. The growth of Squidoo has come from individuals (99%) not corporate partners.

- What you start with is wrong. At least what we started with was. Fortunately, we planned on being wrong, and have revamped most aspects of what we built. Tomorrow I’ll be posting on our new ad approach.

If you want to see what’s working, here are three things to try:

March 15, 2007

Lloyd points us to Makers of Splenda buy Hundreds of Negative Domain Names. The idea, I guess, is to keep someone from writing something nasty about Splenda.

Is there enough money in the world to buy enough domain names to keep a determined person from saying something nasty about Splenda?

Monopolies work to protect something that wouldn’t belong to them if we had a chance to start over. Everyone else works to provide services or goods that people actually want.

Gil just sent this one over:

[Blake just sent me this note: "The reason it is free is because they put their switches in independent telephone companies (rural America) when a larger phone company terminates a call (when you call the “free” conference calling) then the rural company is able to charge Qwest or whomever else terminates the call a fee. In areas like IA they want to buy the LD for .05 cents a minute and then charge Qwest as high as .15 cents a minute for terminating the call. They want to buy it for less then it costs. This is a common practice in this sector of the industry but they have found a way to milk the system and do more then it was intended to do and are in this case killing the larger Telco companies if that makes sense." It’s entirely possible he’s right. If so, I apologize to Cingular, etc.–the challenge those companies face is pretty obvious–we don’t get phone service so we can call most phones, we get it so we can call all phones.]

I’ve been listening to Live at Massey Hall: Neil Young and thinking and even crying a bit. It’s an awfully powerful piece of work.

Two lessons for marketers, one small, the other bigger. First, it’s interesting to note how much more excited and open the crowd is to songs they’ve heard before. Even some of the songs that ended up becoming classics got a tepid reaction because they were unknown at the time.

Second, on songs that aren’t working so well, you will hear Neil try harder, play louder, raise his voice and strain to make an impact. It doesn’t work. At all. It’s what you say, most of the time, not how you say it.

March 14, 2007

I went to trade in my

I went to trade in my car Jay Porter Prius for an updated Prius today. Well, I meant to do that, but I walked out instead.

I arrive at Westchester Toyota and pass two or three salespeople loitering outside. Inside, there were two or three more, sitting in a line of chairs, waiting for the signal from the headmistress at the counter.

My guess is that even for a thriving brand like Toyota, most of these guys weren’t paid so much. They were ‘good’ salespeople, lifers who showed up, did what they were told and closed a sale here and there.

It soon became clear that the salesperson who was assigned to me wasn’t ‘great’. The dealership had messed up: He had no record of my appointment, no file, no history of why I came. But he just punted. He made no effort to engage with me or look me in the eye or empathize with my frustration at the complete waste of time my call yesterday had been. He gave up after about ten seconds, bummed out that he had lost his place in line. So I left.

Driving home, I started to think about the discontinuity in the graph of salespeople. Discontinuities are interesting, because that’s where you can see how a system works. In this case, it’s obvious that a great salesperson is going to sell far, far more than a good one. Nine women working together can’t have a baby in one month, and ten good salespeople still aren’t going to close the account that a great one could. That’s because it’s not a linear scale. The great ones reach out. They work the phones when they’re not first in line. They understand what a customer wants. They’re not just better than good. They’re playing a totally different game.

My best advice: Fire half your salesforce. Then, give the remainder, the top people, a big raise, and use the money left over to steal the best salespeole you can find from other industries or even from your competition. You’ll end up with fewer salespeople. But all of them will be great.

And the good guys? Have them go work for the competition.

March 13, 2007

The first review of The Dip in the mainstream media was from Richard Pachter in the Miami Herald. Given the short length of the book, his ‘review’ was more like half a sentence (Richard promises a complete review soon). But it was a very nice half sentence. Now we have a longer review from the ironic management columnist Lucy Kellaway. (Reg. required). Here’s what she really said,

"This double attack from two friends laid me low for a bit, but I now have the ideal weapon with which to fight back. I’ve been sent a proof copy of a delightfully slim new book by Seth Godin called The Dip – A little book that teaches you when to quit (and when to stick). Godin’s theory is that quitting is a vital part of success. The worst thing any of us can do is to try to be well rounded people: he urges us to concentrate all efforts on the things we are going to win at, and quit everything else."

So maybe the only delightful part was the width of the book, but it’s better than, say, "annoying…" or "plagiarized…"

March 12, 2007

That’s what my book is really about. Or, to be a lot more positive about it, it’s about avoiding temptation and gravity and becoming the best in the world.

I’m amazed at how quickly people will stand up and defend not just the status quo but the inevitability of it. We’ve been taught since forever that the world needs joiners and followers, not just leaders. We’ve been taught that fitting in is far better than standing out, and that good enough is good enough.

Which might have been fine in a company town, but doesn’t work so well in a winner-take-all world. Now, the benefits that accrue to someone who is the best in the world are orders of magnitude greater than the crumbs they save for the average. No matter how hard working the average may be.

I’ve never met anyone… anyone… who needed to settle for being average. Best is a slot that’s available to everyone, somewhere.

I just got a note from Nathan, who asks,

" [I recently realized] that I want to be a marketer. So now with a resume that includes "Research Analyst" for an economics professor, "Finance Director" for a Nevada governor candidate, and a degree in physics from Harvard, I find myself applying for jobs in marketing. Ultimately, I would like to be VP of Product Development or perhaps CEO at a new company (I love bringing remarkable ideas to frutition), and I have suddenly realized marketing, not finance, is the way to go for me. And, as I search for jobs and try to find an entry point for my new found path, I have a few questions:

1. Where do I start? Most of what I read online seems to say I should have had a marketing internship in college. Can get an Assistant Brand Manager position with no experience?

2. Do you have company suggestions? Which companies get that some of the millions they are spending on TV ads could be better spent improving their products/services?

3. Which books should form the backbone of my marketing education?"

My answer is easy to write, harder to implement. In my experience the single best way to become a marketer is to market. And since marketing isn’t expensive any longer (it takes more guts than money), there’s no need to work for Procter & Gamble. None. In the old days, you could argue that you needed to apprentice with an expert and that you needed access to millions (or billions) to spend. No longer.

So, start your own gig. Even if you’re 12 years old, start a store on eBay. You’ll learn just about everything you need to learn about digital marketing by building an electronic storefront, doing permission-based email campaigns, writing a blog, etc. Who knows more about marketing–Scoble or some mid-level marketing guy in Redmond?

You don’t need a lot of time or a lot of money. You can start with six hours every weekend. Over time, if (and when) you get good at it, take on clients. Paying clients. Folks that need brilliant marketers will beat down the door to get at you. After a while, you may decide you like that life. Or, more likely, you’ll decide you’d rather be your own client.

People who want to become great fishermen don’t go to work on a salmon trawler. And people who want to become marketers ought to just start marketing. (Bonus: here is a book list).

Erik points us to: The Internet went down yesterday, and nobody noticed. It’s a good story of hiding as a customer service stragegy, but it’s also interesting to note how our connected world fell apart. My fancy alarm clock (that automatically checks the time) is wrong, my wife’s laptop (that automatically checks the time) is wrong, too.

What happens when we try to do something really complicated?

Graham points to an article by my neighbor: Inside Job: My Life as an Airport Screener. The surprising thing about the theatre isn’t that it exists. The surprising thing is that we’re so bad at it.

It’s easy to get hung up on whether it’s appropriate to put on a show when it comes to airport security or eating at your restaurant or attending your church. But I think it’s more interesting to get past that discussion and instead wonder, "If we’re going to put on a show, how could we do it better?" Starbucks and Disney have both made billions doing just that.

If you and I sat down for an hour, I have no doubt we could dramatically increase the quality of the security show at the airport, or the bureaucracy show at the Department of Motor Vehicles or the litigation show at the local courthouse.

I went to trade in my

I went to trade in my